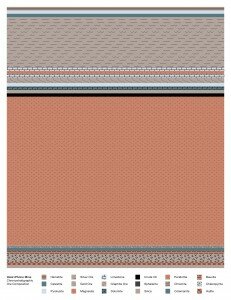

Below is a short text to accompany work by the Artist Erik Wysocan in The Fifth Season, an upcoming group show at James Cohan gallery in New York. The image included here is part of Erik’s work and shows a visual breakdown of the mineral content of an iPhone 3G.

The iPhone 3G, this innocuous and already slightly outmoded little cluster of minerals and marketing is an emblematic meeting point for the material and symbolic processes shaping the contemporary entanglement of social and geologic stratifications: both product and engine of the great cleavages of the global economy, those geopolitical fractures that Marxist critics refer to with euphemistic kid gloves as ‘uneven development’; a treasured possession bound up with resource wars and environmentally destructive extraction practices driven by a rapacious global system of neo-colonial corporate-feudalism; the consumer excretion of a world where exhausted Chinese factory workers are driven to suicide satisfying the herd instincts of those queuing around the block of landmark retail spaces, to be the first to dissect the latest cosmetic innovations in the myopic navel of the Yelposphere; a Trojan horse for the ever increasing marketization of all areas of life and a key instrument in the ongoing erosion of the distinction between work and everything else; a vital tracking device in the fiction that endlessly curating one’s life as a surveillance-ready editorial spread will bear fruit in coherent self realization rather than exponential alienation, no matter how many tinting apps are used to create a trompe l’oeil of ‘authentic experience’.

Its perhaps fitting then that the ubiquitous Apple infused aesthetics of ‘post-internet art’ (those pastel palettes set off against the sterile, ‘Café Gratitude’ transcendence of white plastics; social media sculptures; high-gloss-clean-edged-biomorphic-desk-top ‘objects’, etc) are trending on the art world’s Richter scale (Contemporary Art Daily, e-Flux, etc) with almost synchronized frequency and intensity as the concept of the Anthropocene. This concept – which claims that the human impact on the environment has been so great that it constitutes a new geological epoch legible in the earths’ stratigraphic record – has become something of a curatorial meme, employed to add a dash of deep time drama and geological grandeur to the pervasive, if vague, claim that ours is a ‘post-human’ era when the conceptual and material boundaries between the human and the non-human are in breach.

There has been an unfortunate tendency in some of those areas of critical art discourse where the Anthropocene has gained traction, to use it to frame a mishmash of discussions around non-human phenomenologies, multi-species collaboration and affective sensitivity to the vitality of things, as if what will inevitable emerge in the wake of violent ontological distinctions will be a cozy comfort zone of inclusion and participation (Occupy Noah’s Ark?). However, it seems fair to assume that the planetary convergence of natural and social systems will create a more challenging set of conditions that will test anthropocentric imaginaries more forcefully than any online metaphysics, whilst at the same time withholding the comforting certitudes of apocalyptic thought. Indeed, it is becoming apparent that the feedback from industrial capitalism’s mineral plunder will not be confined to future climate change (another euphemism), but is fueling a planetary-scale mass extinction already well underway. The catastrophe is not an event but a process, but this doesn’t mean time is a buffer: it is already here and must be lived.

Although the ‘post-human’ reception of the Anthropocene in art discourse often risks reducing a number of conflicting ideas in to a bland stew of Zeitgesity references, the coarse logic of its contemporary appeal can nevertheless be understood. Indeed, the iPhone 3G and the Anthropocene might conceivably be understood – albeit through the epistemological smoke machine of news cycles, tweeter feeds and press releases – as two figures pointing to processes that radically decenter the human subject, or at least the individualist lodestar of liberal modernity, from its tradition seat of power, no matter how different in geographic scale or historical importance those processes may be. Viewed in this light, the increasing penetration of technological mediation into the social constitution of the self, via lifestyle support appendages like iPhones, is mirrored by the inhuman forces of the earth erupting within the social domain, insofar as the centrality of the human subject is cast in doubt in both instances. But what such discussions make clearest of all is that the Anthropocene has not, at least thus far, gained any epistemological leverage on the subjective myopia of late liberalism, and has more often then not been used as mock up ‘white people’s problems’ as geological Grand Guignol.

Almost every discussion of the Anthropocene evokes the image of the earth shot from space, and indeed the first issue of the newly launched journal, The Anthropocene Review, featured just such an imagine on the cover. Likewise, the default screen for the iPhone is one of NASA’s famous ‘Blue Marble’ images, although a version from 2002 centered on north America appears here rather than the original 1972 image centered on Africa and the Arabian peninsula – the California Ideology having come full circle with Stewart Brand’s ‘Whole Earth’ finding its spiritual home in Steve Jobs’ Apple. It would be of course easy to spin this as the perfect symbol of a hubristic era failing to heed the dire warning written in the rocks – the earth, totally ‘enframed’ in technological systems and reduced to a ‘world picture’, can be slipped in to any pocket with cocksure confidence that Man has mastered Nature with Technology: a planet domesticated on an interface. However, it seems unlikely that many would think of the earth this way today as they scroll past the latest numbing headlines from the IPCC, proving what they are already bored of knowing. Perhaps then the iPhone’s Blue Marble is better understood as a reassuring totem of a pre-Anthropocene belief in the human capacity to manage a harmonious earth, a sort of civilizational pacifier for the anxious subjects of late liberalism – those who are exhausted from having so much on their plates, and are pretty sure we are fucked anyway.

Excellent piece, Rory. Definitely resonates with Colebrook’s recent “Essays on Extinction”. As Colebrook suggests, “…it follows that far from being an ecological figure that will save us from the ravages of globalism, subjectivism and bio-politics, it is the image of the globe that lies at the center of an anthropocentric imaginary that is intrinsically suicidal.”

“Art, the Anthropocene and the iPhone 3G – Erik Wysocan (feat. Rory Rowan)” http://t.co/OZj1uwyQke